Sometimes, being told to “just breathe!” ranks in my Top 10 Most Irritating Phrases Ever.

It’s one of those things that’s easy to say, and nearly impossible to implement in the moment that it matters. It’s a correction that I would get at least ten times every ballet class, and it’s a phrase I find myself repeating when I’m trying to move deeper into an asana while practicing yoga.

Breathing is supposed to be one of the most– if not the most– natural tasks for a living organism to perform. And yet, as dancers, why is it that we struggle so much to breathe through our movements? In this installment of Relearning the ABCs, we’ll dive into the mechanics of breathing and how they are altered during movement. In the following post in this series, we’ll explore the ramifications of not breathing while dancing (spoiler alert: there are quite a few), understand what exactly deep core breathing is, and look at an embodied approach to tackling this common correction.

The Anatomy of Natural Breath

In 1950, Arthur B. Otis, Wallace O. Fenn, and Hermann Rahn published Mechanics of Breathing In Man, claiming that the movements of breathing had been minimally studied by physiologists. These authors go on to state that the air breathed in by man must encounter some “viscous and turbulent resistance” while working around several “resisting forces.” Though perhaps a bit dramatic in initial description, I can’t help but think that Otis, Fenn, and Rahn stumbled upon the key issue with breathing while dancing; specifically, in how we generate even more “viscous and turbulent resistance” while performing sweeping port de bras and holding developpés.

Breathing, or technically referred to as ‘respiration,’ is officially termed the act of inhaling oxygen from the atmosphere, and exhaling carbon dioxide. As simple as this definition may be, it is much more than a simple swap of one gas for another. Respiration, and your respiratory system, involves multiple structures: the nose, pharynx, larynx, trachea, bronchi, and lungs, to name a few. Respiration has a major effect on the cardiovascular activities of the body as well– think back to using deep breaths to slow your heart rate, or how your heart rate skyrockets after an intense petit allegro combination.

Lungs themselves are delicate organs, especially given how integral they are to our lives. The right and left lung actually differ from one another, with the right lung having three lobes (sections, or divisions), while the left consists of only two. When you inhale from the mouth or the nose, the air travels into your body, down the windpipe– the trachea– and enters the lungs through the bronchi tube. Once the air has entered your lungs, it gets shuttled through a system of smaller and smaller tubes, finally ending up in the air sacs, or alveoli. It’s here that the swap between oxygen and carbon dioxide occurs.

In fact, while you’re reading this, try it out. See if you can feel the rush of air in through the nose, and the swell of your chest as it passes through these structures. Maybe even try seeing if you can catch yourself paying attention to how you’re breathing as you go about your daily tasks.

Breathing is a Great Activity. “Sucking In” the Stomach is NOT.

Contrary to popular belief, breathing is actually an action. It isn’t something that passively happens– but why?

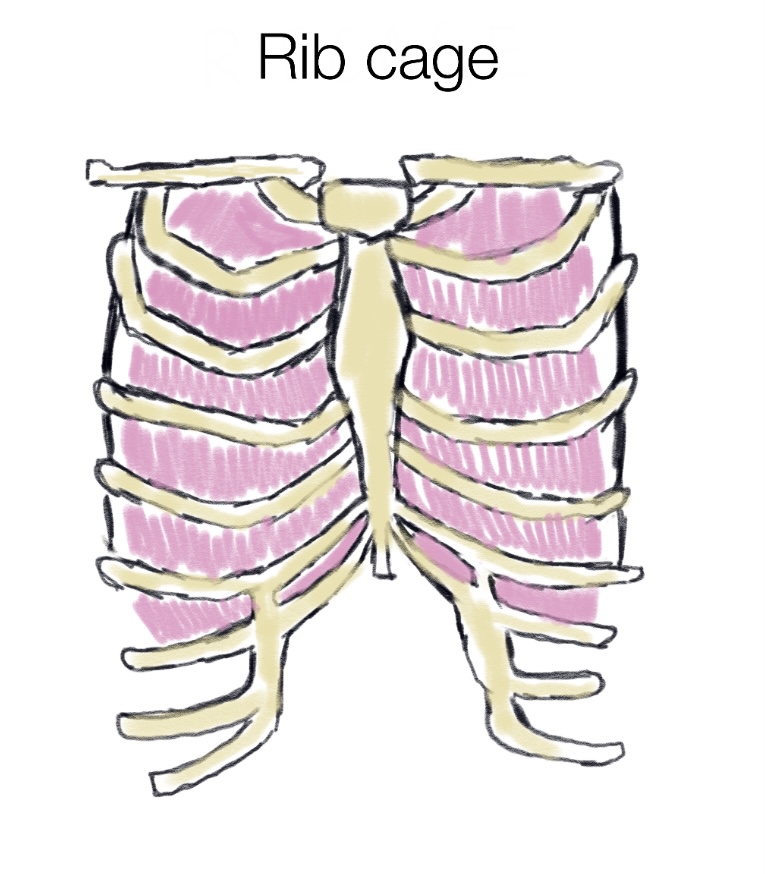

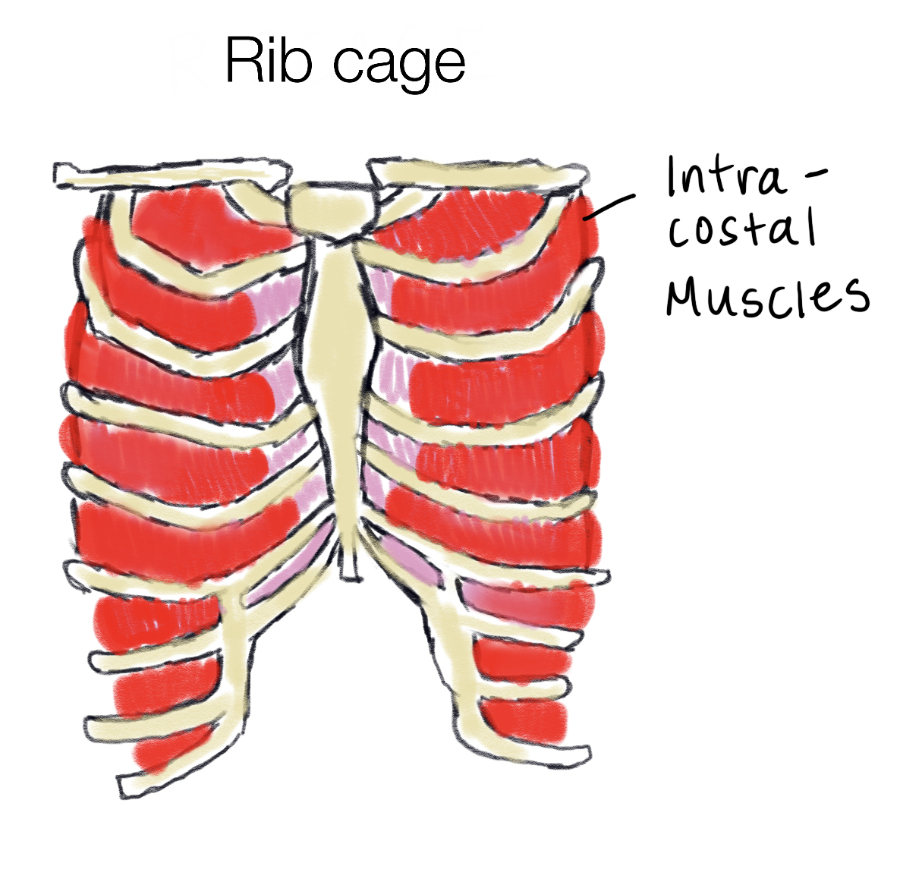

Consider the anatomy of your ribcage, for a moment. Your delicate lungs are housed within the ribcage. The ribcage is flanked by inner and outer intercostal muscles that expand and contract with the rise and fall of your chest. The diaphragm sits just under. Your transverse abdominis, often referred to as the ‘deep core,’ sits layered towards the middle, covered by the external oblique muscles towards the sides of the body and the rectus abdominis muscle right on top.

In sum, there’s a whole LOT of muscle layered into your torso, and implicated in the way we breathe.

The ribcage expands to accommodate the increase in the volume of the thoracic cavity, but it needs muscles to help those bones move around. When air is moved into the lungs– also known as inspiration– muscles like the diaphragm and the intercostals are contracting to allow for the expansion to happen.

This awareness is what deep core breathing is all about!

A lot of dancers have the tendency to just “suck in” the stomach while dancing, and that’s one of the least helpful things that a dancer can do. Trust me. I used to do it all the time. By trying to “suck in,” you’re putting a lot of undue tension into the chest-neck area instead of allowing the breath to naturally flow through. “Sucking in” is often conflated with an engaged core, but finding that distinction is almost impossible when most dancers don’t even understand WHAT an engaged core is! Hint hint… it has to do with that pesky transverse abdominis that I mentioned.

In the next post in this series, we’ll discuss how to combat “sucking in” with the engaged core, and how it can make you a more energetic, dynamic dancer.

Don’t hesitate to leave comments and contribute to this discussion if you are so inclined to do so!

More Readings & Resources

Check out these links if you’d like to learn more about the anatomy of breath. This post was a very, very simple overview of the basics– but sometimes simple is best when we’re trying to apply a new concept.

If you’re interested in reading more about what Otis, Fenn, and Rahn had to say, check this out:

https://journals.physiology.org/doi/abs/10.1152/jappl.1950.2.11.592

This book, titled “The Human Respiratory System: An Analysis of the Interplay between Anatomy, Structure, Breathing and Fractal Dynamics” by Clara Mihaela Ionescu is absolutely fabulous if you have a science background and you’re interested in learning more about the physiology of breath. The full PDF is available here.

And finally, in case you’re interested in the evolution of respiratory systems in different organisms, check out this great paper by Klein and Codd.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1569904810001552

Leave a comment